“On Background” is a series of blog posts wherein I talk about the books, films, and other media that would come to inform me in writing WE TAKE CARE OF OUR OWN. My gratitude to the authors, journalists, filmmakers, and thinkers responsible for these works is hereby assumed.

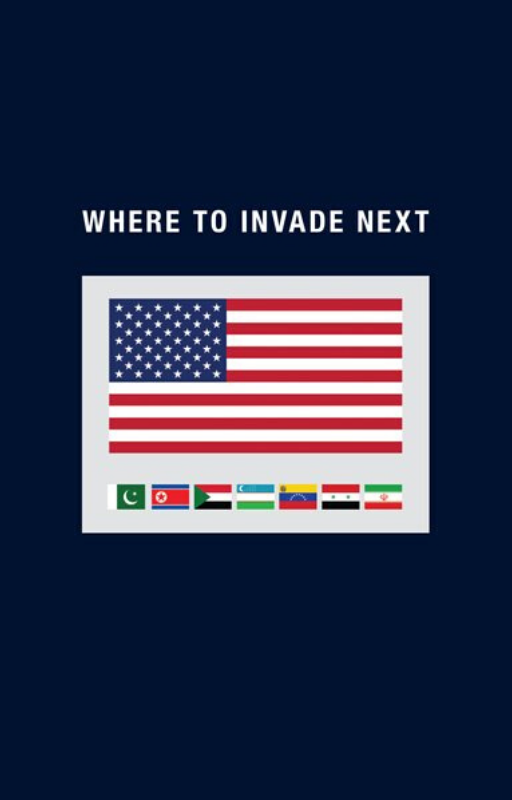

Not to be confused with the 2016 Michael Moore documentary of the same name, Where To Invade Next is a 2007 collection of essays written by Jason Roberts, Eric Martin, Andrew F. Altschul, Peter Rednour, Greg Larson and Jesse Nathan (with help from a team of researchers) and compiled and edited by Stephen Elliott.

The seven essays run about 10 pages apiece, and all are titled with the names of countries, that in the aftermath of 9/11 were put on notice for their tendency to undermine America’s approach to freedom and human rights: Iran, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Syria, Sudan, and North Korea.

Each essay follows the same general pattern. After a quick Introduction detailing where in the world the country is located and what the political landscape looks like there, a detailed Threat Overview offers a summary of what makes the country so dangerous to U.S. foreign interests, whether it’s that nation’s links to terrorism, its overly ambitious nuclear goals, its partnering with other “usual suspect”-type countries, and so on. Then it’s on to Popular Measures that our Armed Forces might take, should we find the nation in question further destabilized by extremism. Then it’s a quick Conclusion to send the reader off concerned, yes, though never shaken in his or her resolve to support America’s quest to defend freedom from her many existential threats.

That’s it. Morality, practicality, long-term effects—these issues are left for the politicians, the historians to worry about.

One might be wondering why McSweeney’s, a non-profit (!) publishing house headquartered in San Francisco (!!) that the New York Times once dubbed “too cool for words” (!!!), would be interested in putting out an ultra-dry collection of facts and figures, devoid of commentary or context, exploring the feasibility of siccing the American war machine on a bunch of Second and Third World countries?

As it turns out, all the commentary/context one needs is provided by a 2007 quotation from General Wesley Clark, which serves as the epigraph of Where to Invade Next and which I will reproduce in full here:

About ten days after 9/11, I went through the Pentagon and I saw Secretary Rumsfeld and Deputy Secretary Wolfowitz. I went downstairs just to say hello to some of the people on the Joint Staff who used to work for me, and one of the generals called me in. He said, ‘Sir, you’ve got to come in and talk to me a second.’ I said, “Well, you’re too busy.’ He said, ‘No, no.’ He says, ‘We’ve made the decision we’re going to war with Iraq.’ This was on or about the twentieth of September…

“So I came back to see him a few weeks later, and by that time we were bombing in Afghanistan. I said, ‘Are we still going to war with Iraq?’ And he said, ‘Oh, it’s worse than that.’ He reached over on his desk. He picked up a piece of paper. And he said, ‘I just got this down from upstairs’—meaning the Secretary of Defense’s office—’today.’ And he said, ‘This is a memo that describes how we’re going to take out seven countries in five years.'”

And so, with this one quotation, the achievement of Where To Invade Next becomes clear. The essays create an incomplete yet compelling portrait of the hysteria that injected itself into American foreign policy in the days immediately following the 9/11 attacks, an hysteria that would lead to a memo describing how the U.S. Armed Forces might “take out” seven countries in five years.

I touch on something similar in my novel (We Take Care of Our Own, coming out 2020 via Montag Press). The world wherein my characters exist is dominated by a superconglomerate of the nation’s largest military, technology, energy, and media providers that has effectively “taken over” the War on Terror. Such mass privatization has, naturally, caused the War on Terror to be expanded into several new countries/markets, including: Afghanistan, Iraq, Iran, Syria, Lebanon, Pakistan, Uzbekistan, Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Somalia, New Zealand, and the Amazon Basin. And, as the novel begins, public sentiment is turning toward war in Tasmania.

OK, obviously, waging war in some of those countries is absurd. New Zealand, for instance, has done nothing to antagonize the U.S. in its whole history.

But that’s supposing that American foreign policy can boast some degree of consistency. Consistency is policy, after all.

And we’re talking about a United States of America that, removed from the horrors of 9/11 by two decades, has just in the last year 1) placed a targeted hit out on an officer of a legitimate foreign government for reasons that have yet to be cited, 2) seriously if not formally entertained the idea of purchasing the autonomous Danish territory of Greenland, and 3) officially launched a new military branch to prepare for war in (or is it with?) outer space. Consistency no longer applies; absurdity has become commonplace.

In the end, Where To Invade Next can be described as a purposely numbing document exploring one way in which money + fear + firepower can come to serve an absurd, terrible goal. For all its baked-in shortcomings as an engaging read, it nevertheless remains necessary to a deeper understanding of the dangers of mass hysteria, once institutionalized.