I have written three novels so far in my life, though We Take Care of Our Own will be the first one to get published (via Montag Press, later this year). The two others will likely never be published, unless I happen to strike serious artistic pay dirt at some point in the future, and then after my death some enterprising small publisher decides it’s worth their time and effort to sift through my personal archives to unearth, edit, and publish Animals in Heaven and/or Maggie.

I don’t envy this purely hypothetical small publisher—Animals in Heaven, my first, might actually be readable, in places, but I’m not sure it rises to the level of novel. There’s no overarching story to it, and nothing truly vital or important is ever at stake. It’s more like a couple of hundred pages about the same three or four people.

Successor Maggie I’m actually kind of proud of for the first hundred pages or so, but then what had up to that point been passing for a story comes up against the author’s need to Make Stuff Happen, and so the last 50 pages is this confusing welter of flashbacks, flash forwards, actions without motivation, and twists without explanation. It’s been a long time since I’ve looked at Maggie but I bet I can pinpoint the exact paragraph where things start to go off the rails.

In any case, I had learned quite a bit about what not to do by the time I got up and running with We Take Care of Our Own. One of the main things I had learned was the importance of keeping things straight, that is, making sure my characters are all operating under the same laws of time and space. You can’t have one character graduate high school, attend a two-year college, find a job as a marketing director for a large corporation, rise through the ranks, and take over the CEO position while his sister spends an afternoon reading a book. What I needed was a timeline, a place where I could keep my characters’ stories straight and be able to see them all at the same time.

The Writer as God (Not the God. I don’t think.)

The writer must be prepared to act as God for his characters—the ability to all at once see his or her characters’ pasts, presents, and futures is a necessary aspect of this, shall we say, authorial divinity.

So I did what any struggling writer might do: I started drawing lines across sheets of paper, then marking them with notes describing the important events of each character’s life. The problem was, I had at least half a dozen important characters, all of whose timelines I needed to keep meticulously organized if the overarching story was to work, so the shortcomings of my sketchy approach became apparent after about 10 minutes.

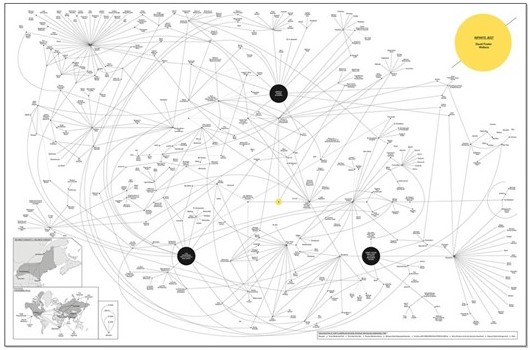

Incidentally, I have hanging in my home office a poster designed by artist Sam Potts that that shows not so much a timeline but the various 200 or so characters (and their relationships to one another) in David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest. It is awesome and hilarious in its intricacy:

Granted, We Take Care of Our Own isn’t quite the postmodern opus that Infinite Jest is (though its scope is every bit as ambitious, I would argue). Still, I needed a better timeline maker than pencil and paper could provide.

Enter Preceden

Preceden specializes in timelines. I would recommend it for any writer who’s having trouble keeping his characters’ stories straight. Feel free to check out my We Take Care of Our Own characters’ timelines here.

Not that I imagine anyone ever noticing, but there’s a good chance that, even amid the beautifully formatted timelines offered by Preceden, I still have a few time-sensitive mistakes. I chalk that up purely to my own fallibility, or the fact that I’ve made some edits in the text without going back to mark them in my Preceden timelines.

But you know what? It doesn’t matter, because I never mention the exact year in which We Take Care of Our Own takes place. Instead I turn to a practice used often in works of fiction throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, that is, replacing the year with a couple of underscores. Why this was done I don’t know, and it looks like the Internet doesn’t know either.

Hence, the year in which my novel takes place is FY20__, as opposed to 2032, as you can tell in my Preceden timeline. (That “FY,” in case you were wondering, stands for Fiscal Year, because, in this world, everyone uses the fiscal calendar. Crony capitalism run amok and all that.) Is this redaction a comment on humanity’s living in a post-history society? An assertion that the dystopia of We Take Care of Our Own may not await us in the future but may already be upon us? Sure, OK! But you and I know that first and foremost it was a practical means of covering my (b)as(e)s.